TEMPLES

The temple is the most important institution on Bali and the center

of religious activities. Though Bali is renowned as the "Land of Ten

Thousand Temples," there are actually at least 50,000 scattered over

the island. Large or small, simple or elaborately carved, they're everywhere-in

houses, courtyards, marketplaces, cemeteries, and rice paddies; on beaches,

barren rocks offshore, deserted hilltops, and mountain heights; deep inside

caves; within the tangled roots of banyan trees. At most intersections

and other dangerous places temples are erected to prevent mishaps. Even

in the middle of jungle crossroads, incense burns at small shrines brightened

with flowers, wrapped leaves, and gaily colored cloth.

Each village has its own shrines for community

worship, and public temples may be used by anyone to pray to Sanghyang

Widhi or any of his manifestations. There are mountain temples (pura

bukit), sea temples (pura segara), genealogical temples, temples

for the deities of markets and seeds (pura melanting), lake temples,

cave temples, hospital temples, bathing temples, temples dedicated to spirits

in springs, lakes, trees, and rocks. There are also private temples for

those of noble descent, royal "state" temples, and temples for

clans (pura dadia) who share a common geneology. Some temples commemorate

the deeds of royalty. Numerous important temples-Gunung Kawi, Pura Penulisan-are

actually memorial shrines to ancient rulers and their families.

Balinese temples are not dedicated to a specific

god but to a collection of spirits, both good and bad, who reside in the

various shrines. No one knows which spirits are visiting which shrines,

so to make sure that only their beneficent aspects appear offerings are

placed in all shrines.

Unlike the austere, restricted temples of

other countries in Asia, the Balinese temple is open and friendly, with

children, tourists, and even dogs wandering in and out. During festivals

the temple grounds serve as a stage where the worshippers become actors,

the priests directors, and the gods and demons invisible but critical spectators.

Once every six months in the Balinese calendar,

each temple holds an odalan or anniversary celebration. Since there

are tens of thousands of temples on the island, an odalan is in

progress almost every day somewhere. On the occasion ancestral personages

descend from heaven and the temples are alive with fervent activity. For

the really big religious ceremonies and rites, temple pavilions are sometimes

completely wrapped in cloths and umbel-umbel banners, studded with

ceremonial umbrellas. Foods are placed on altars under the eyes of the

stone deities, the gods occupying small gold, bronze, or gilded wood figurines

(pratima). During festivals the temple courtyard is literally covered

in gifts to the gods, with seething throngs of people beneath high tapering

white and saffron-colored flags, the air thick with smoke and the clanging

of gamelan. Everyone arrives beautifully dressed, presenting the

deities with prayer, devotions, food, music, and cockfights to amuse them

during their visit to Earth. Temple dances like the pendet and rejang

welcome and delight the visiting spirits. After one to three days, thoroughly

entertained and surfeited with food, the deities return to heaven.

Temple Etiquette

Anyone who's properly dressed may visit a temple. If you're wearing

long pants or a long skirt, a sash will usually be required; if you're

wearing shorts, you'll need a sarong. Tour guides provide these

items, as do ticket-sellers at many of the most-visited temples. Best is

to buy your own in the local market for around Rp5000. Sashes should also

be worn for any temple festival you may happen upon.

All temple complexes and historical sities

now charge Rp550 admission. If there's no entrance fee, you may be asked

for a small contribution to help offset the cost of maintenance. It's also

common to sign a guestbook. At some of the more obscure sites beware of

guestbooks in which zeros have been added to all the preceding figures,

making it appear donations have been substantial.

Use your camera with discretion. Don't climb

onto temple buildings or walls, or stand or sit higher than a priest. If

people are praying, avoid getting between them and the direction in which

they're praying. Stealing is unthinkable. In 1993, 14 people were murdered

on the spot after they were caught stealing from temples in the Ubud area.

Non-Hindus may not enter the innermost courtyards (jeroan) of some

temples. Tour companies are now starting to drop Brahman temples from tours

at the request of temple keepers. By ancient law menstruating women are

banned from temples, due to a general sanction against blood on holy soil.

Temple Types

Bali is a floating shrine, where all the homes are temples and all

the temples homes. Thousands of private domestic temples-sanggah,

or pamerajan for the upper castes-are dedicated to various deities

and family ancestors. Each small domestic altar is very well maintained

and receives fresh offerings each morning. Every house has a small shrine

(sanggah paon) by the hearth dedicated to Bhatara Brahma, the god

of fire, and yet another by the well dedicated to the god of water, Bhatara

Vishnu. Temporary shrines (sanggah crucuk) are constructed for special

purposes, such as a death in the family or before work commences on a project.

Every Balinese village features at least

three obligatory temples-in the north, center, and south of town. The pura

puseh is the "navel" temple, or temple of origin, around

which the original community sprang. This temple is dedicated to the spirits

of the land, to the deified village founder, and to Vishnu, the Preserver

of Life. The pura desa, or "village temple" is concerned

with everyday village matters and ritually prescribed village gatherings.

Dedicated to Brahma, the creator, the pura desa is also an assembly

hall where men meet for communal, ceremonial meals. Also called the pura

balai agung, it's oriented to the mountains and to the east. The temple

of the dead, pura dalem, is dedicated to Shiva the Destroyer or

his consort Durga. It is also connected with ancestors. As most villages

are built on a slope, the southern or kelod end in the lowest part

of the village is where the temple of the dead and the burial ground with

its mournful kepuh tree are located. Each faces the sea, where the

powers of the netherworld dwell. The pura dalem's carved walls are

often decorated with explicit pornography and gruesome depictions of the

fate awaiting offenders who violate taboos or fail to observe customs.

Before the deceased have been completely purified by cremation, their souls

rest in the death temple. The pura dalem is also where the sacred

barong mask is stored. In some villages a single temple functions

as both pura puseh and pura desa, with only a wall dividing

them.

Agricultural temples are also important.

All over Bali are pura dedicated to the rice goddess, Dewi Sri,

divine consort of Dewa Vishnu, the Preserver. In northern Bali, where subak

control every facet of life, the elaborate temples dedicated to Dewi Sri-called

here Pura Hulun Swi-are the grandest religious edifices on the island.

Pura Ulun Danu Bratan in Candikuning and

Pura Luhur on Gunung Batukau are dedicated to lake goddesses worshipped

as sources of fertility. These are deemed female temples; their male counterpart

is Pura Besakih on the slopes of Gunung Agung. Also widespread are the

subak temples belonging to local irrigation societies.

Known as the "Six Great Sanctuaries,"

Sad-kahyangan temples are the holiest places of worship on Bali.

Owned by the whole island rather than by individual villages or clans,

they're also known as "State Temples," or by the even more pretentious

designation "World Sanctuaries."

Visitors are sometimes confused to hear of

as many as 12 sites listed among the "Six Great Sanctuaries,"

a result of regional favoritism. Most important is Besakih, the great mother

temple complex on the slopes of mighty Gunung Agung. This volcano, the

"Navel of the World," is Bali's holiest mountain, where all the

gods and goddesses live. Others among the six include Pura Panataran Sasih

in Pejeng, Pura Dasar in Gelgel, Pura Panataran Goa Lawa in Klungkung,

and Pura Kehen in Bangli.

Also included-depending on who's counting-are

the magnificent Uluwatu sea temple on the Bukit Peninsula, built on a long

narrow cliff 76 meters above the sea; Pura Tirta Empul in Tampaksiring,

famous for its sacred pool; Pura Sakenan on the island of Serangan; Yeh

Jeruk in Gianyar; and Pura Batukau near the top of Gunung Batukau in Tabanan.

|

|

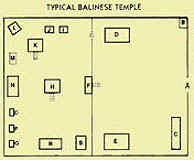

Jaba means

"outside." This is the first courtyard of a Balinese temple.

One enters it through the split gate (A) or candi bentar. It serves

as an antechamber for social gatherings and ritual preparations. Contains

thatched-roofed storage sheds, bale for food preparation, etc.

Jeroan means "inside."

The inner courtyard of a Balinese temple, the temple proper. Here are all

the shrines, altars, and meru towers that serve as temporary places

for the gods during their visits to Bali. This enclosure, behind the closed

gate (paduraksa), is the "holy of the holiest."

A) candi bentar -The split gate, two halves of a solid,

elaborately carved tower cut clean through the middle, each half separated

to allow entrance into the temple. Its form is probably derived from the

ancient candi of Java.

B) kulkul - a tall alarm tower with a wooden split drum,

to announce happenings in the temple or to warn of danger

C) paon - the kitchen, where offerings are prepared

D) bale gong - a shed or pavilion where the gamelan is

kept

E) bale - for pilgrims and worshippers

F) paduraksa - A second, closed ceremonial gateway, guarded

by raksasa, leading to the inner courtyard (jeroan). This

massive monumental gate is similar in design to the candi bentarbut is

raised high off the ground on a stone platform with a narrow entrance reached

by a flight of steps. Often behind the door is a stone wall which is meant

to block demons from entering the jeroan This gate is only opened

when there's a ceremony in progress.

G) side gate - aIways open to allow entrance to the jeroan

H) paruman (or pepelik) - a pavilion in

the middle of the jeroan which serves as a communal seat for the

gods

I & J) shrines for Ngrurah Alit and Ngrurah Gede, secretaries

to the gods, who make sure that the proper offerings are made to the gods

K) gedong pesimpangan - a masonry building with (usually)

locked wooden doors dedicated to the local deity, the ancestor founder

of the village

L) padmasan - the stone throne for the sun-god

Surya, almost always located in the uppermost right hand corner of the

temple, its back fadng the holy mountain Gunung Agung. Sometimes there's

a shrine for Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma here as well.

M) meru - a three-roofed shrine for Gunung Agung, the

holiest and highest mountain of Bali

N) meru - an 11-roofed shrine dedicated to Sanghyang Widhi,

the highest Balinese deity

O) meru - a one-roofed shrine dedicated to Gunung Batur,

a sacred mountain in northern Bangli Regency

P) Maospait Shrine - dedicated to the divine settlers

of Bali from the Majapahit Empire. The symbol of these totemic gods is

the deer, so this shrine can be recognized by the sculpture of a deer's

head or stylized antlers.

Q) taksu - The seat for the interpreter of the deities.

The taksu inhabits the bodies of mediums and speaks through them

to announce the wishes of the gods to the people. Sometimes the medium

is an entranced dancer.

R & S) bale piasan - simple sheds for offerings

|

Temple Layout

Balinese temples are derived from the Neolithic sanctuaries of prehistoric

Bali. Like the primitive stone enclosures and platforms of ancient Polynesia

and Micronesia, the aboriginal prototype of the Balinese temple was a rectangle

of holy ground containing sacrificial altars and crude heaps of stones.

Ancient Balinese temples evincing this strong Polynesian feeling are found

either in the mountains or along the coast.

Some mountain villagers still practice ceremonies

echoing back to prehistory, when through shamanistic rites the spirits

of fearsome nature gods would visit the megaliths. The shrines in courtyards

of contemporary temples can be traced back to these rough stone pyramids.

In many cases, craftsmen have added new stonework, cement altars, and fresh

decorations, often hiding the original work. The terraced layout of such

temples as Pura Kehen and Pura Besakih also suggest very early origins.

The Bali Aga still build distinct temples

with such odd features as little bridges and separate halls for priests

and other groups. See the great temples of Trunyan on Lake Batur and Taro

in the mountains behind Gianyar.

Though a "typical" Balinese temple

does not exist, the innumerable temples of Bali generally share a number

of characteristics. In contrast to China, India, or Hinduized Java, where

the temple is a roofed hall with a statue of a god as its focus of religious

worship, on Bali space is emphasized over mass. A requirement for any consecrated

place on Bali is that it be an open area enclosed by walls; the interior

space is holy ground, as sacred as the shrines within; the temple is open

to the sky, to make the shrines more accessible to the gods. A replica

of a lake or mountain may be placed in a temple to save devotees the time

and effort of visiting the actual sacred site.

The Balinese temple consists of two or three

walled-in courtyards. Jabaan, the outermost yard, is used for offerings,

dances of a secular or commercial nature, and by musicians. Jaba tengah,

the middle yard is dedicated to food preparation, the making of offerings,

and classical dances. Jeroan, the innermost yard is the locus of

worship, ceremonies, and sacred dances. Elaborate stone gates lead from

one courtyard to the next. All courtyards are oriented in the kaja

direction, toward the sacred mountains, and worshippers always face kaja

when they pray.

Temples are also divided into vertical layers

of spirituality-the higher the tower, the more sacred the shrine. A distinctive

Balinese structure is the pagoda-like meru, with as many as 11 (always

an odd number) superimposed black thatch roofs. The top roof is the perch

for the particular god when s/he descends. Most "seats" for deities

are located at the end of the temple nearest the mountains. The last courtyard

is the most sacred; to enter this inner sanctum, worshippers often must

pass through an enormous gate under the threatening gaze of the fanged

guardian demon Boma. In the belief that evil spirits cannot turn corners,

numerous temples feature a solid brick wall just behind the entrance.

One of the most familiar Balinese architectural

features is the remarkable split gateway (candi bentar), a tall

monument cut exactly down the middle, its walls rising to an ornamental

peak, always facing the sea. The large gap symbolically separates the two

halves of the Indic cosmic mountain, Mahameru. An instantly recognizable

emblem of Bali, this sacred structure often serves inappropriately as an

entrance gate to hotels, palaces, and government offices.

Northern Bali's temples embody yet another

design, which departs dramatically from those of the temples of the south.

Here, richly carved stone monuments are often built on the slope of a hill,

accessible by long flights of steps. Pura Meduwe Karang in Kubutambahan

and Pura Beji in Sangsit are two outstanding examples of this style. These

architectural extravaganzas contain many humorous relief panels in which

European technology and burlesque caricatures coexist together in the spirited

world of Balinese mythology.

Temple Construction

No special class of architects constructs temples. The master sculptor

who designs and directs the work takes part in the backbreaking toil, assisted

by a number of stone and brick masons. He sometimes works from a blueprint,

but more often the temple is begun without a drawn plan. Possessing skills

passed down through generations, the master builder claims to know the

traditional proportions and specifications of a temple "in his belly."

In traditional temple construction all units of measurement are based upon

the sculptor's own body. This unscientific yet flawless technique assures

that no two temples share the same dimensions.

The aesthetics of a temple are judged by

its symmetry and harmony with its surroundings. Blocks of stone and baked

bricks are joined without mortar and must fit together perfectly to give

the structure strength. Stone surfaces are worn by rubbing them together

while sluicing them with water. After the mass of stones and red brick

are fitted, work begins on the extravagantly sculpted decorative motifs

and reliefs.

Balinese temples are constantly being cleaned,

rebuilt, and restored. Because the gray sandstone in the temples of southern

Bali wears out, every temple must be completely renewed at least once every

50 years. In 1993, a small community of 250 people near the village of

Mas raised 12 million rupiah to rehabilitate their banjar temple.

With the growing use of ferro-concrete form construction, traditional temple

building is becoming a lost art.